Military Veteran Identities

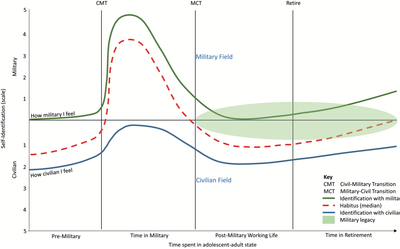

In the pre-military phase, the level of how military a person feels will increase as they consider enlisting and then rises sharply after basic training. Very quickly the person feels almost totally military, but the model acknowledges that military personnel still retain aspects of their civilian lives whilst serving. How military a person feels while serving diminishes as the time served goes on and the model illustrates that during an individual’s time in service there is a shift toward the pull of civilisation and the pull factors of returning to civilian life take hold. The model also indicates that during post-military working life elements of the military identity remain and the prominence of the military identity starts to increase once again toward the end of working life and increases further in retirement.

Integration back into civilian society at the end of military service must take place, and the military person becomes a veteran, there is a return to normal life and according to Iversen and Greenberg (2009) ‘in the UK despite the press focus on negative outcomes for war veterans, the limited existing evidence suggests that the majority do well after leaving the armed forces (p 101). This is not a simple exercise, however, and the transition back to civilian society can be as abrupt as the transition from civilian to military.

The military legacy creates problems for veterans during transition and into later life, the Ashcroft (2014) report found that while most service leavers smoothly transition to civilian life a lack of housing, finance, employment and lack of community were concerns around dealing with civilian life. Some participants in this study said that they felt civilian employers would not employ them. According to Ahern et al. (2015), they have a disconnection from civilians, a lack of purpose in civilian life, and a lack of purpose-connected feelings, contributing to a significant communal effort, deserved recognition, and appropriate management of mental health problems.

In addition to issues surrounding transition the veteran community, in recent years has felt the need to turn to activism and protest to have their voice heard as they feel they are being discriminated against with a hunt to prosecute veterans who served in conflict zones. The newspaper articles of Dixon (2018) and Scarlett (2020) describing attempted prosecution for alleged historical crimes committed during the Northern Ireland conflict whilst an amnesty for terrorist groups has been put in place is an example of this.